Testing Test Helpers

Writing tests for code you ship is a good thing to do. It helps verify that you didn’t ship bugs. It helps you verify that you fixed a bug that was previously shipped. You’re not infallible, and tests help prevent mistakes by serving as an executable way to verify the code matches your expectations. In recent years, I’ve come to extend this practice to include most test helpers.

Looking just to copy the test helper code? Look at the code in the conclusion.

What is a Test Helper?

A test helper is component to remove boilerplate from the test, or otherwise make the test easier to understand. For example, consider the following bit of implementation and test code:

// IncrementerComponent.swift

final class IncrementerComponent: NSObject {

let counter = 0

let label: UILabel

init(button: UIButton, label: UILabel) {

self.label = label

button.addTarget(self, action: #selector(buttonHandler(_:), for: .touchUpInside)

}

@objc private func buttonHandler(_ button: UIButton) {

counter += 1

label.text = "\(counter)"

}

}

// IncrementerComponentTests.swift

final class IncrementerComponentTests: XCTestCase {

var subject: IncrementerComponent

var label: UILabel!

var button: UIButton!

override func setUp() {

label = UILabel()

button = UIButton()

subject = IncrementerComponent(button: button, label: label)

}

func testOnInitializationSetsLabelTextTo0() {

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "0")

}

func testIncrementsLabelWhenTapped() {

button.sendActions(for: .touchUpInside)

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "1")

}

func testIncrementsLabelWhenTappedAgain() {

button.sendActions(for: .touchUpInside)

button.sendActions(for: .touchUpInside)

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "2")

}

}

The repeated use of button.sendActions(for: . touchUpInside), while relatively short, conceptually gets in the way with interpreting the test. Each time you come back to this, you have to remember that button.sendActions(for: . touchUpInside) means that you’re tapping the button. Additionally, because sendActions(for:) takes an argument, you might slip up and accidentally use one of the other UIControl.Event values. Lastly, simulating button taps is a very common thing to do in test. It would save time, make the tests easier to understand, and prevent bugs to create a test helper that does this for you.

When to make a Test Helper

When considering whether to create a test helper, ask yourself: Will it make the tests easier to understand? Will it help reduce boilerplate while writing tests? Will it help save time while writing tests? The first one is especially important. Tests are written to be executed by machines, but read by humans. Anything you can do to make understanding what’s going on easier is a boon.

Creating a Test Helper

With that in mind, I think that extracting out sendActions(for:) into a tap method on UIButton makes sense:

extension UIButton {

func tap() {

sendActions(for: .primaryActionTriggered)

}

}

As we'll see in a little bit, this test helper doesn't work in certain, important, cases.

This uses the newer UIControl.event.primaryActionTriggered semantic event to send actions, which should hopefully be more future-proof for sending events like this.

When to write Tests for a Test Helper

Before we refactor IncrementerComponentTests to use this new helper, we should consider writing a test to verify that tap() works as we expect it should. Not all test helpers need their own tests. Some are very specific and will only be used in a place where it will be easy to diagnose when they fail. My personal rule-of-thumb is that once a component is going to be used in more than 1 place, it needs its own tests. 1 This applies to production code and test code.

Testing the Test Helper

In this example, there’s only 1 component to even use tap(), but simulating taps in a UIButton is a very common thing, and if this were a real app, we’d be using tap() all over the place. So, tap() meets the criteria to have its own tests. While we’re writing these, let’s also verify that we correctly respond to the .primaryActionTriggered event, as well as utilizing the UIAction API.

private class ActionRecorder: NSObject {

let calls: [UIButton] = []

@objc func tapHappened(_ button: UIButton) {

calls.append(button)

}

}

final class UIButtonTapTests: XCTestCase {

func testSendsTouchUpInsideUsingUIAction() {

var calls = 0

let subject = UIButton()

subject.addAction(UIAction(title: "") { _ in

calls += 1

}, for: .touchUpInside)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(calls, 1)

}

func testSendsPrimaryActionTriggeredUsingUIAction() {

var calls = 0

let subject = UIButton()

subject.addAction(UIAction(title: "") { _ in

calls += 1

}, for: .primaryActionTriggered)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(calls, 1)

}

func testSendsTouchUpInsideUsingTargetAction() {

let subject = UIButton()

let recorder = ActionRecorder()

subject.addTarget(recorder, action: #selector(ActionRecorder.tapHappened(_:)), for: .touchUpInside)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(recorder.calls, [subject])

}

func testSendsPrimaryActionTriggeredUsingTargetAction() {

let subject = UIButton()

let recorder = ActionRecorder()

subject.addTarget(recorder, action: #selector(ActionRecorder.tapHappened(_:)), for: .primaryActionTriggered)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(recorder.calls, [subject])

}

}

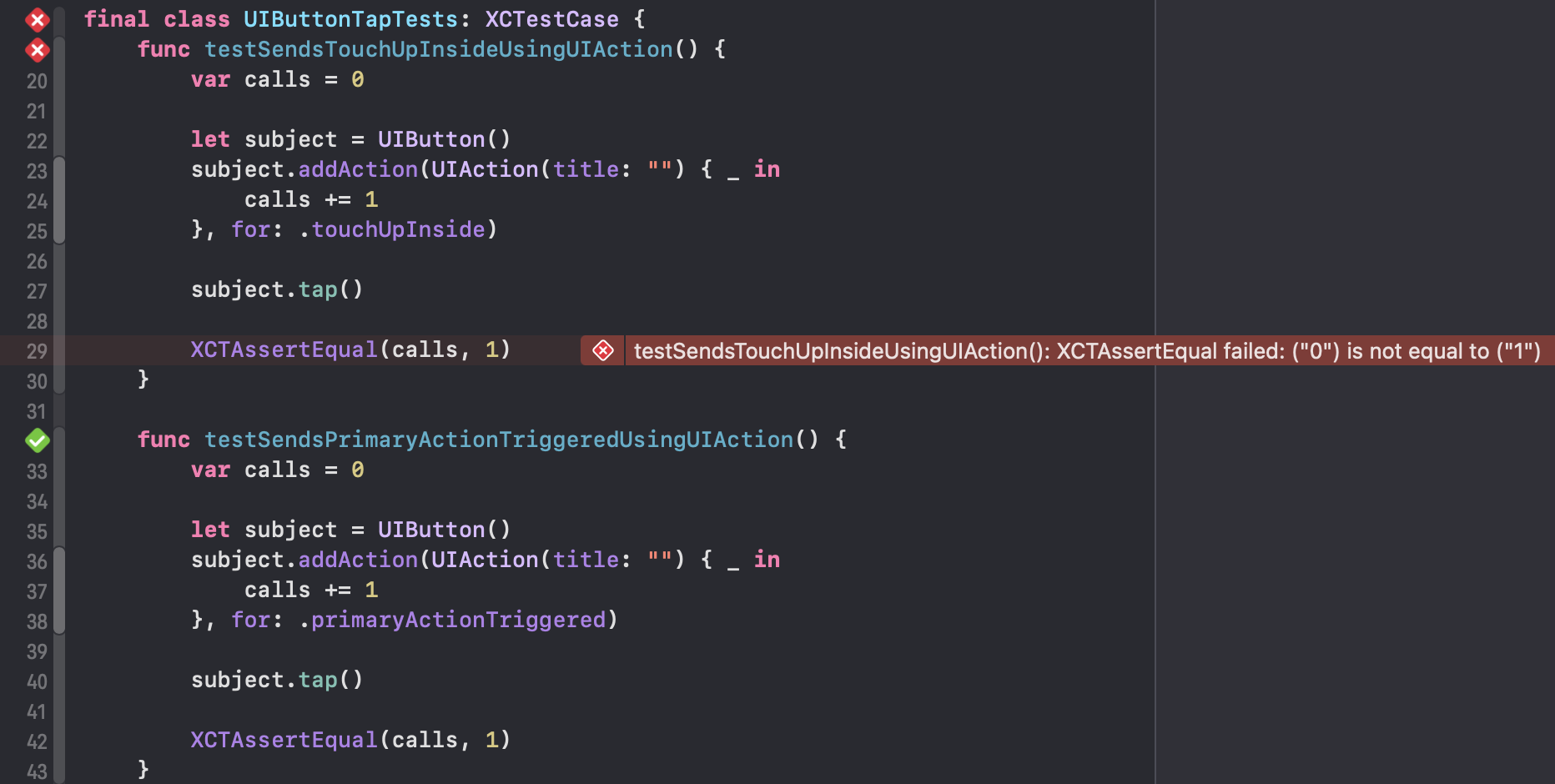

With that written, we can run the tests to verify that tap works and… it fails. Huh. 2

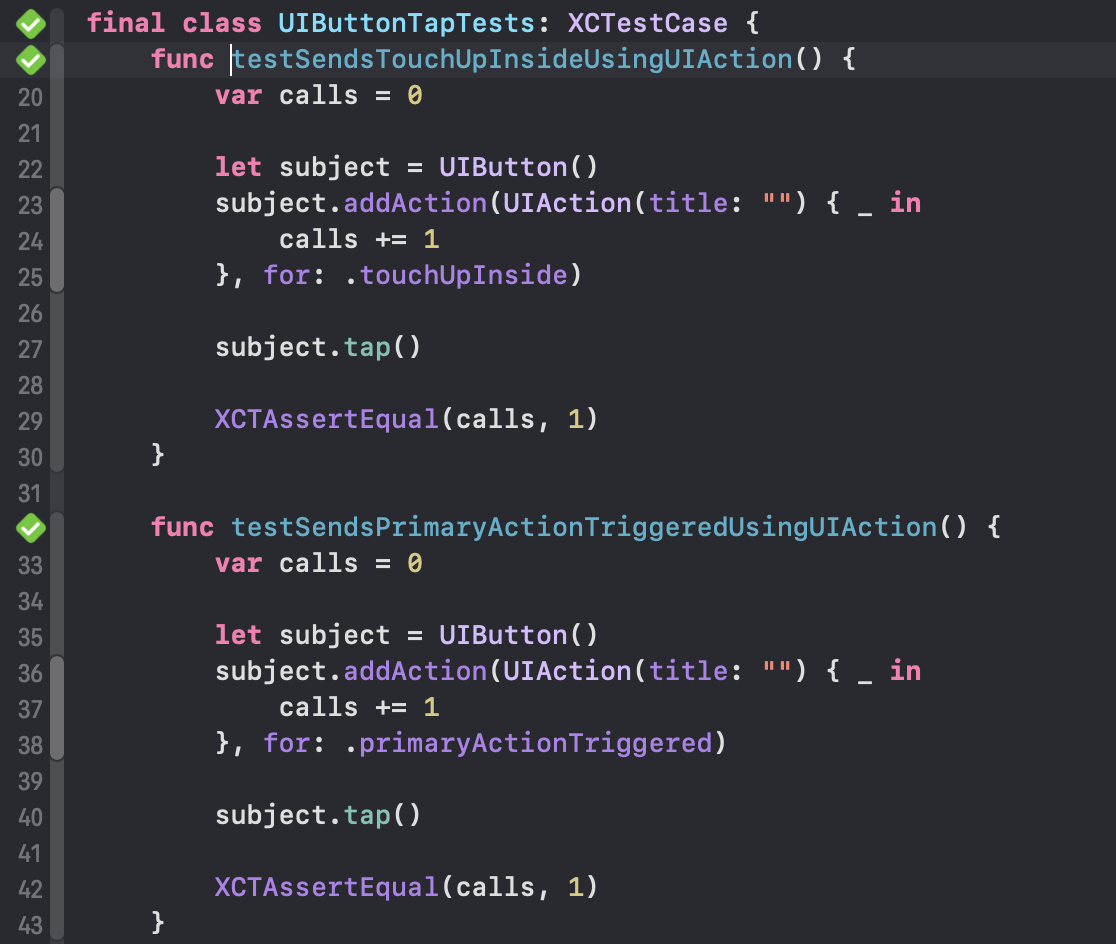

Looking at the failing tests, it appears that sending UIControl.Event.primaryActionTriggered doesn’t send callbacks to events registered to .touchUpInside. We could change everywhere we registered to receive a button press to use .primaryActionTriggered, but I wonder what happens if the test helper sends .touchUpInside.

And that passed!

Interesting, our first implementation of tap() would have caused pretty significant frustration if we had deployed it widely. When a test fails, you expect it to be something in the code being tested. Certainly not a 1-line test helper like this. Only after trying to revert back to directly calling sendActions(for: .touchUpInside) would we have realized the issue was in the tap helper.

Conclusion

With this out of the way, we can deploy the new tap() handler, and see it work in the wild:

// IncrementerComponent.swift

final class IncrementerComponent: NSObject {

let counter = 0

let label: UILabel

init(button: UIButton, label: UILabel) {

self.label = label

button.addTarget(self, action: #selector(buttonHandler(_:), for: .touchUpInside)

}

@objc private func buttonHandler(_ button: UIButton) {

counter += 1

label.text = "\(counter)"

}

}

// IncrementerComponentTests.swift

final class IncrementerComponentTests: XCTestCase {

var subject: IncrementerComponent

var label: UILabel!

var button: UIButton!

override func setUp() {

label = UILabel()

button = UIButton()

subject = IncrementerComponent(button: button, label: label)

}

func testOnInitializationSetsLabelTextTo0() {

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "0")

}

func testIncrementsLabelWhenTapped() {

button.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "1")

}

func testIncrementsLabelWhenTappedAgain() {

button.tap()

button.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(label.text, "2")

}

}

// UIButton+TestHelpers.swift

extension UIButton {

func tap() {

sendActions(for: .touchUpInside)

}

}

// UIBUtton+TestHelpersTests.swift

private class ActionRecorder: NSObject {

let calls: [UIControl] = []

@objc func tapHappened(_ control: UIControl) {

calls.append(control)

}

}

final class UIButtonTapTests: XCTestCase {

func testSendsTouchUpInsideUsingUIAction() {

var calls = 0

let subject = UIButton()

subject.addAction(UIAction(title: "") { _ in

calls += 1

}, for: .touchUpInside)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(calls, 1)

}

func testSendsPrimaryActionTriggeredUsingUIAction() {

var calls = 0

let subject = UIButton()

subject.addAction(UIAction(title: "") { _ in

calls += 1

}, for: .primaryActionTriggered)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(calls, 1)

}

func testSendsTouchUpInsideUsingTargetAction() {

let subject = UIButton()

let recorder = ActionRecorder()

subject.addTarget(recorder, action: #selector(ActionRecorder.tapHappened(_:)), for: .touchUpInside)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(recorder.calls, [subject])

}

func testSendsPrimaryActionTriggeredUsingTargetAction() {

let subject = UIButton()

let recorder = ActionRecorder()

subject.addTarget(recorder, action: #selector(ActionRecorder.tapHappened(_:)), for: .primaryActionTriggered)

subject.tap()

XCTAssertEqual(recorder.calls, [subject])

}

}

Now IncrementerComponentTests is much easier to understand, and we have a new test helper that can be used to elsewhere we want to verify what happens after a button is tapped.

I hope this sufficiently demonstrates the value of testing your own test helpers. It’s not that much extra effort, and knowing that your tools work as they’re supposed to pays off in spades when you’re diagnosing and debugging failures.

-

This is very similar to my rule for when to pull out a

privateAPI of some component into apublicone of a dependency. Once aprivateAPI is called from more than 3 places, it needs to be pulled out into apublicAPI with its own tests. ↩ -

This is something I learned while writing this. For UIButton (as of iOS 17, beta 2),

.touchUpInsidealso means.primaryActionTriggered, but.primaryActionTriggereddoes not also mean.touchUpInside. Wild. ↩