What Airplane Building has Taught me about Project Management

For the past year, I’ve been working on building my own airplane. I am not very far along. Of the 26 chapters in the plans (of which the first 3 are now-outdated administrative details, a materials list, and how to work the materials), I have completed roughly 75% of chapter 4. Put another way, I have another 21.25 chapters to complete. I’ve been at this for a year 😭. However, this does mean that I’ve learned a lot about how not to manage such a large project.

One Step At A Time

This is a very large project. I expect it’ll take me at least another 3 or 4 years to complete, assuming no major setbacks. How do you deal with such a daunting endeavor? You do one thing at a time. Eventually, you’ve done enough that you have an airplane. Related advice in the homebuild aircraft community is to do at least one thing a day for the project. Even if it’s only for 5 minutes, that’s 5 minutes you’re further along.

Build or buy tools to speed things up

The right tool can literally save you hundreds of hours, and be the difference between enjoying work and dreading it.

One of my favorite tools is an oscillating multitool. This thing is great. With the correct blade attachment, it cuts through fiberglass like butter. Just that alone has shaved off hours of using a knife to trim fiberglass. I also have a sanding attachment for it which is faster than hand-sanding, and more precise than an orbital sander. It is such a versatile tool which has saved me so much time. Totally worth the cost.

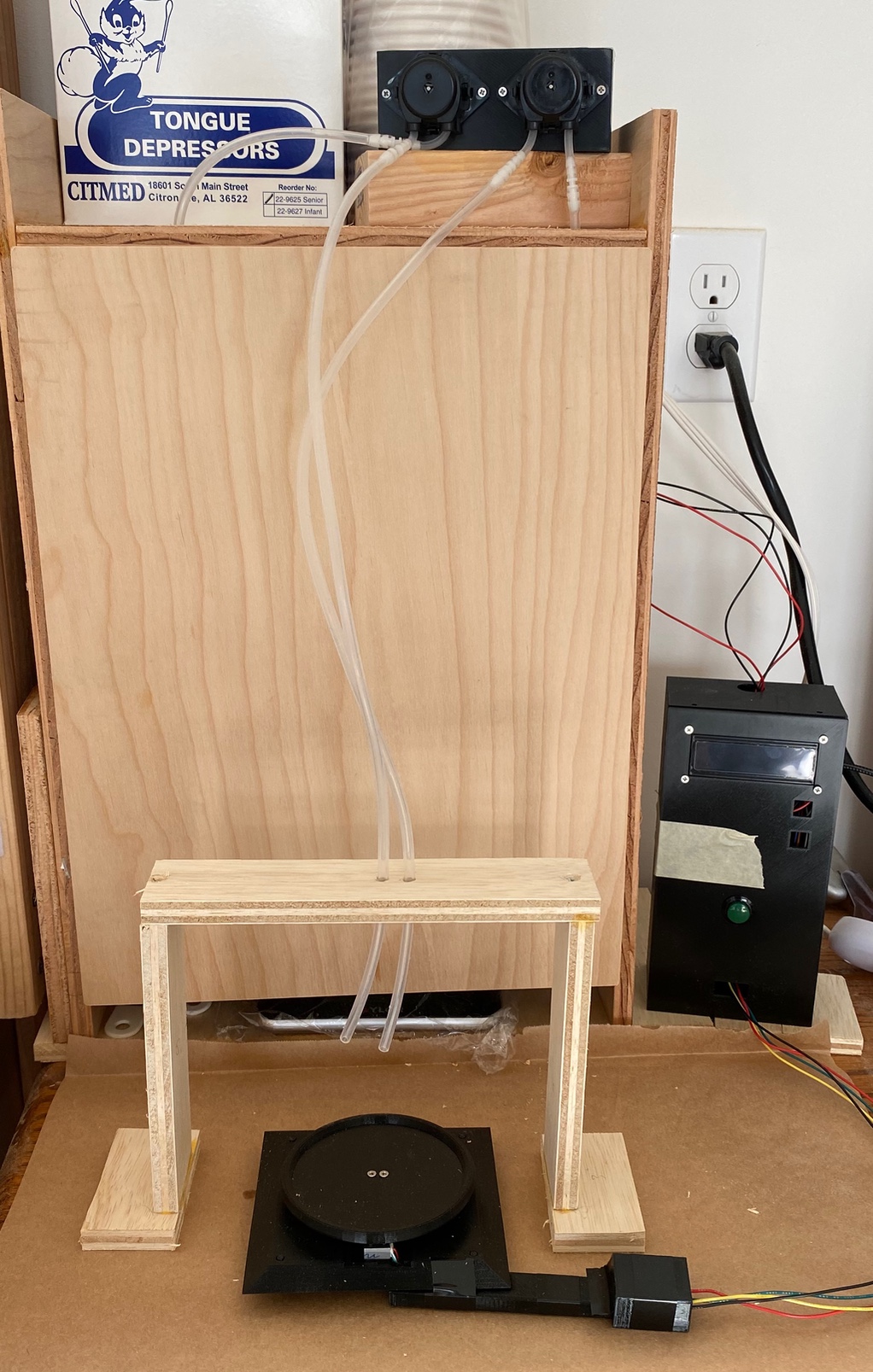

Another favorite tool is one I built: an automated epoxy dispenser. I’m going to use a lot of epoxy in this build. I don’t particularly enjoy the process of pouring it. There are a number of ways I could address this, and I chose to do so with this little box. With the press of a button, this thing dispenses 120 grams of 2-part epoxy for me. It’s incredibly slow, and I still have to mix the dispensed epoxy together. But it dispenses the correct amount of epoxy each time, and it automates a process I’d rather not do.

The point of both of these anecdotes: Don’t be afraid to spend time or money on tools that can improve your efficiency and productivity. In almost every case, it’s worth it.

Outsource if Necessary

Don’t suffer from Not Invented Here syndrome. Don’t be afraid to outsource work.

Starting at the beginning of May, I purchased a set of mostly-finished wings, and foam cores for the horizontal stabilizer for my airplane. I reached out to a guy who has a business selling CNC-cut foam cores for the wings and horizontal stabilizers. He just happened to have the wings available. So I bought those and took delivery a month and a half later. By my estimate, this will save me around a year’s worth of build time. Totally worth what I paid for these.

Don’t be afraid to outsource and pay other people to do things for you, or to purchase things from vendors when it makes sense.

Minimize Blockage

The main reason homebuilt airplanes don’t get finished is because they take too long. Waiting on external factors is one of the biggest slowdowns there is. You lose momentum and interest when you can’t or don’t work on it. A large part of why I still have a lot left to do despite being at this for a year because I was blocked. At first I was waiting for my first shipment of material to arrive; A couple months later it got too cold for me to work epoxy in my then-unheated workshop. It’s way too easy to let time pass by without doing anything.

I solved both of these issues by throwing money at the problem. 2 month wait for material to arrive? Order material long before you need it. I’d much rather have the problem of storing this stuff than be blocked waiting on material. Can’t do work because it’s too cold? I had a minisplit installed in the workshop; now it’s fully climate-controlled. Most of my progress has happened in the 2 months since I had that minisplit installed.

Do whatever it takes to remove sources of blockage.

There will be Setbacks Learning Opportunities

This lesson is two in one. The obvious one is to accept that you will make mistakes. You will have to redo some work, or repair a part after you’ve made it. The second lesson is to try not to view these mistakes in a negative manner. Especially early on when you’re doing things you’ve likely never done before. Instead, view these mistakes as learning opportunities. Mistakes will happen, but the real mistake is not learning anything from it.

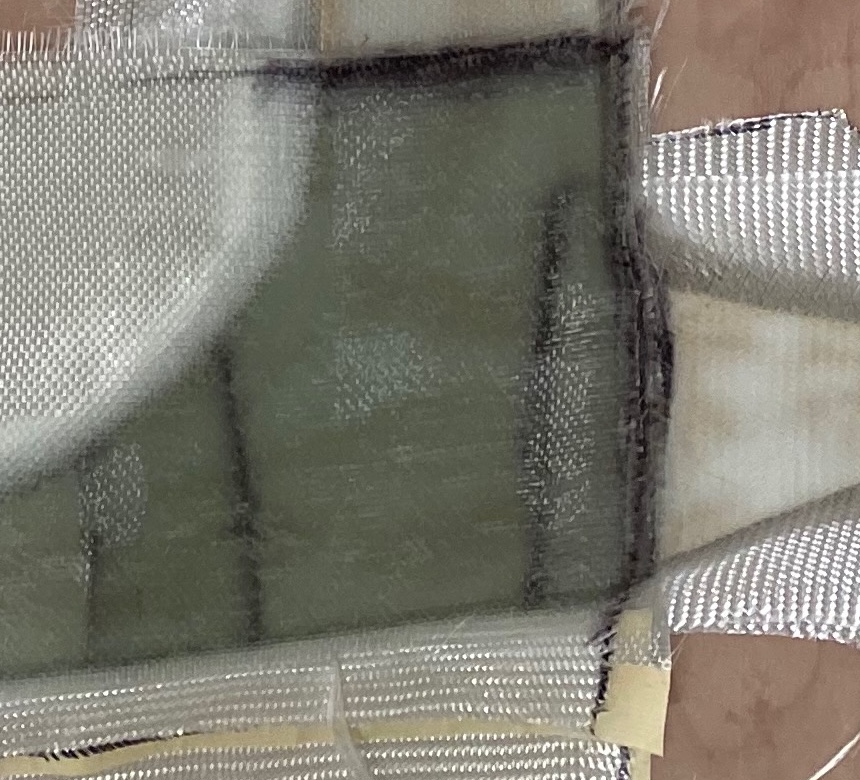

To illustrate: Once I installed my minisplit, I was very gung-ho about getting back to work and making things. Below is an image of one of the first parts I made that weekend.

Upon reviewing this after it cured, I discovered that I had introduced enough errors in the layup - especially on these extra layers on the outside edges - that I was probably better off redoing the part entirely rather than attempting to repair it.

These are especially visible in this zoomed-in portion, where you can much more clearly see both trapped air bubbles - as evidenced by lighter parts in the layup - as well as areas where I didn’t use sufficient epoxy, as evidenced by the areas with a more glossy shine. The rest of the part looks a little better than this, but there are enough visible errors that I’d rather not try to repair it, and instead redo it entirely.

This taught me to both review layup procedures again, as well as investigate ways to better prevent this. As a result, I’m currently experimenting with a form of vacuum bagging. I plan to make use of that technique when I fabricate the replacement part.

Mistakes will happen, don’t let them get you down. You only wasted your time if you didn’t improve from it.

Wrapping Up

This past year has, in many ways, been a crash-course in how not to complete an airplane. Some of these lessons I did right from the start. Others I learned the hard way.

I have a build log available at coz-e.rachelbrindle.com which better details my progress in this. I also tweet about this, and I most of my instagram nowadays is build updates.